The Mystery of Abraham’s Circumcision

In our series of guest blogs, we are proud to introduce a contribution by a ‘friend of the Parable Project’: dr. Ronit Nikolsky. Dr. Nikolsky is an assistant professor at the University of Groningen. She is an expert on midrash and is interested in the themes of cognitive science of religion and the cultural study of emotions. In this blog, she discusses the circumcision of Abraham and his ‘master’, God…

“Walk before me and be whole”, says God to Abraham (Gen 17:1-2) “and I will make my covenant between me and you…”. “This is my covenant which you shall keep”, continues God, after listing his promises and prophecies to Abraham, “every male among you shall be circumcised”.

Basing itself on this biblical narrative, circumcision has become the signifier of the Jewish male in rabbinic culture.[1] In a composition from the Tanchuma-Yelammedenu literature we find a parable which labels Abraham’s circumcision as ‘God’s mystery’:

“I will make my covenant [between me and you]” (Gen 17:2). This is what the scripture says: “The secret of the Lord is for those who fear him [and he makes known his covenant to them]” (Ps 25:14).

And what is the secret of the Holy One Blessed Be He? [It is] circumcision, as the Holy One blessed be He did not reveal the mystery of the circumcision [to anyone] except Abraham, as the scripture says: “The secret of the Lord is for those who fear him” […]

He (i.e. God) said to him: It is enough for a slave to be like his owner.

This is comparable to a king who had a friend who was rich more than enough.

The king said: What shall I give to my friend? He (already) has gold and silver, slaves and maidservants and livestock.

So I will gird him with my zona (girdle).

Thus said the Holy One Blessed Be He [to Abraham]: What shall I give you? I already gave you silver and gold, servants and maids, and livestock, as it is said “Abraham was very rich” (Gen 13:2). What shall I give you? It will suffice you that you will be like me, as the scripture says: “and I will make my covenant [between me and you]” (Gen 17:2).

This is the meaning of “the secret of the Lord is for those who fear him”.

(Tanchuma Buber Lekh Lekha 23)

The parable, as well as the nimshal explain that when God said that the slave (i.e. Abraham) to be like his master (i.e. God), he meant that the circumcised Abraham will be like Him, i.e. God. This entails that God is circumcised, and this is the mystery of the circumcision.

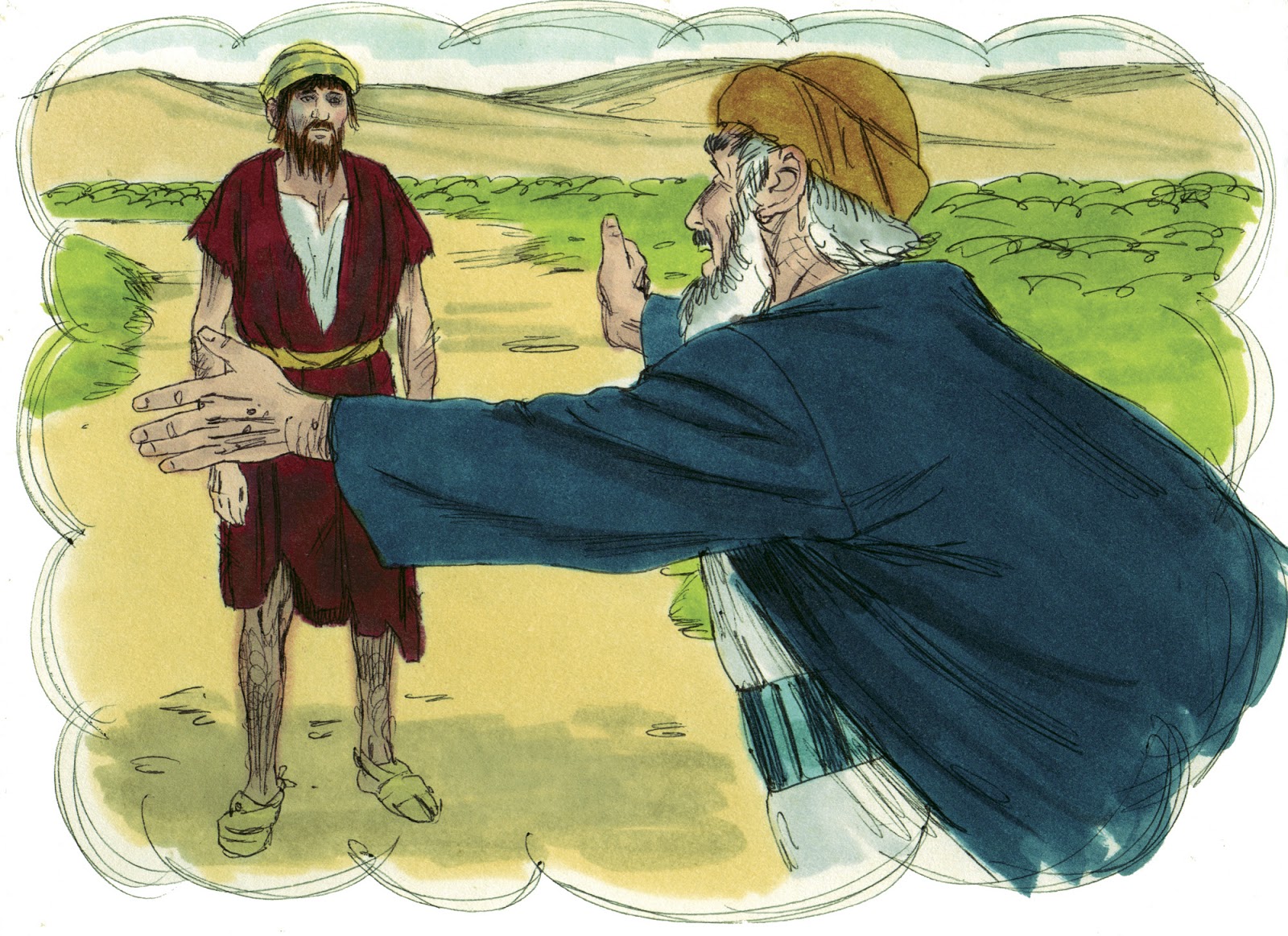

Circumcision of Abraham, from the Bible of Jean de Sy, ca. 1355-1357

What strikes the modern reader of this parable as strange – or even unacceptable – is the idea that God is circumcised. However, from the point of view of a Jewish person of Late Antiquity, this is not at all strange. Conceiving of God in anthropomorphic term is the common practice in rabbinic culture, and as living before the Byzantine iconoclasm, and the Medieval scholastic philosophy, the rabbis, unlike us, found no harm or contradiction of thinking of God in terms of human form (albeit without material representation of it). So while speaking of God’s private parts was not a prevailing practice in rabbinic literature, it would be self-evident that God is circumcised, as the words from Avot de-Rabbi Nathan[2] demonstrate: “Adam was created circumcised, as it says: “God created Adam in his own image” (Gen 1:27)”. What is unusual, and unique to the Tanchuma-Yelammedenu literature, is labeling the circumcision a mystery. This labeling did not originate in rabbinic culture.

The Tanchuma-Yelammedenu Literature is a Jewish homiletic genre from roughly the Byzantine period and mostly from the Land of Israel; it has a strong affinity with synagogal literature and other Jewish circles. Where, in Jewish circles of Late Antiquity or Byzantine period, do we find such an attitude toward circumcision, from which the Tanchuma-Yelammedenu literature could have borrowed? We find it in Sefer Yetzirah. This is not a rabbinic book in any way; it is a sapiential text written in Hebrew, with a strong Neoplatonic, and Neopythagorean mathematics and cosmology at its background. The composition is of an unknown date, but Saadya Gaon, (882-942), wrote a commentary on Sefer Yetzirah, and attributed ancient authority to it, which gives us the terminus ad quem for its composition. The book tells about how God created the world using basic units of letters and numbers. This is secret knowledge, says Sefer Yetzirah, which should not be told to anyone. Surprisingly, Abraham joins the scene in the last paragraph. He is a practitioner who acted on the basic units, and, unlike others, he succeeded. He therefore merited a revelation of God, in which God also makes a covenant with Abraham; this covenant, as can be guessed was sealed with the circumcision. Here is the passage from SY:

[§61; 6.4] When Abraham our father … investigated, and understood, and carved, …, and combined, and formed, and succeeded, the Lord Of All was revealed to him. And He made him sit in His lap, and kissed him upon his head. He called him His lover [cf. Isa 41:8], and … He made with him a covenant between the ten toes of his feet – it was the covenant of circumcision …

So, although the word mystery is not mentioned in the text, SY frames Abraham’s circumcision in a secretive context. Therefore, the aspect most interesting about the parable from Tanchuma-Yelammedenu is that it points to connection between circles that are based in rabbinic culture, with the Jewish circles in which Sefer Yetzirah, a text which on the face of it seems quite foreign to rabbinic culture, was circulating.

Ronit Nikolsky

References

[1] Catherine Hezser, Rabbinic Body Language : Non-Verbal Communication in Palestinian Rabbinic Literature of Late Antiquity (Leiden, Boston: BRILL, 2017)., 48; Howard Eilberg-Schwarts, God’s Phallus, and Other Problems for Men and Monotheism (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994)., 163-196.

[2] Avot de-Rabbi Nathan version A, chapter 2, p. 12, New York, Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), Rab. 25.

A version of this blog post was published earlier at https://confabulatingapge.wordpress.com/2020/07/11/the-mystery-of-abrahams-circumcision/

Recente reacties